Philippe Ledent (ING): “Financing new supply chains will be head-splitting”

After several difficult years, the transport and logistics market seems to be recovering. ING expects a – moderate – recovery from the second quarter of 2024. However, will it be enough to meet the challenges looming on supply chains? Not only the energy transition will require huge investments, but also deglobalisation. With Philippe Ledent, Senior Economist at Log!Ville supporting Partner ING Belgium, we discover the macroeconomic factors affecting the logistics world today and tomorrow.

“Today we are seeing the first signs of a turnaround,” says Philippe Ledent. “2023 was a bad year for transport and logistics with low activity, but this year should gradually recover.”

First the corona crisis, then the energy crisis

To explain, he takes us back to past years. “After the corona crisis, we observe a clear decline in inventories due, on the one hand, to the resumption of activity and the growing demand for goods; and, on the other, to the global problems that arose in supply chains. The last two years, on the other hand, inventories were at a very high level. A major reason was that after the covid crisis, demand for services such as travel, concerts and restaurants rose sharply, to the detriment of goods. The high stocks and weaker demand landed the manufacturing industry in a recession, which in turn weighed heavily on the transport and logistics sector.”

Last year, the energy crisis added to this, which exploded the costs of companies in the EU zone (and to a lesser extent the US) and affected their competitiveness. This was certainly felt in business confidence, which hit a low in mid-2023. Activity fell in both the manufacturing and logistics sectors, which in turn translated into a rise in inventories.

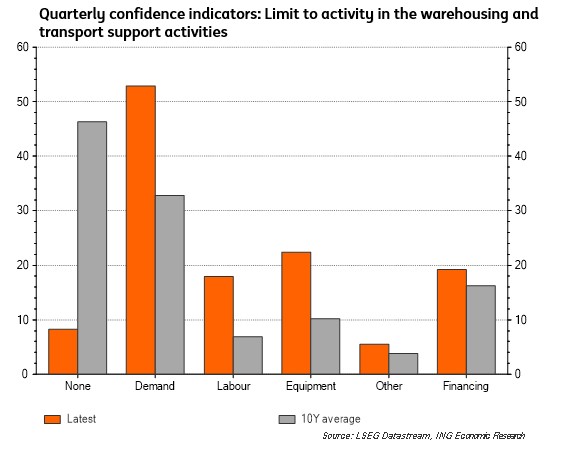

“In 2023, we saw that all indicators continued to decline. The last quarterly survey of 2023 showed that the elementary reason for the decline of logistics activity (and transport) was a decrease in demand. Other factors were at play in that decline, such as the shortage of staff and equipment, and financing problems. These were not due to access to money but to interest rates. Interest rates remained very low for years. The rise posed a problem for the logistics sector, as investments in that sector tend to be long-term,” Ledent said.

Gradual recovery in 2024…

Although indicators in the last quarter of 2023 pointed to weak demand and a downturn in the economy, Ledent is looking at 2024 with quite a lot of confidence. “We are indeed more optimistic. Industry is reviving a bit, so related services such as transport and logistics will follow. By the way, we see this in inventory levels, which are cautiously moving in the better direction,” he says.

“So a positive correction is emerging, with us expecting the recovery to be more evident during the second quarter. The good news is that inventories are falling again, indicating that we are cyclically behind the trough,” Ledent notes.

… but not all the problems are gone

Nevertheless, he remains very cautious. “It is not because we foresee a recovery that all problems are gone. The cost of energy, despite the decline, still remains at a high level and labour costs also remain high. This is true not only in Belgium, but throughout the eurozone, especially compared to Asia and the United States. In Europe, companies are also held back by the fact that they are subject to more regulations than elsewhere,” he notes. “That makes us expect a revival of the economy and of logistics activity, but not a strong acceleration and certainly not a ‘boom’.”

For the logistics sector, the moderate scale of the recovery poses a series of financial challenges, especially in the medium and long term. Ledent cites energy transition and deglobalisation in particular.

Electrification through ambitious regulation

The energy transition in supply chains will initially be felt in the transport sector. ING recently published a paper on the evolution of the truck market in Europe, which also analyses the rise – imposed or not – of electric trucks.

“Many hauliers are still hesitant to invest in electric trucks, mainly because of their price and operational complexity. They will have to change tack in the fairly short term, though. Not because they will be obliged, but indirectly because European rules for manufacturers and shippers will force them in that direction,” says Ledent.

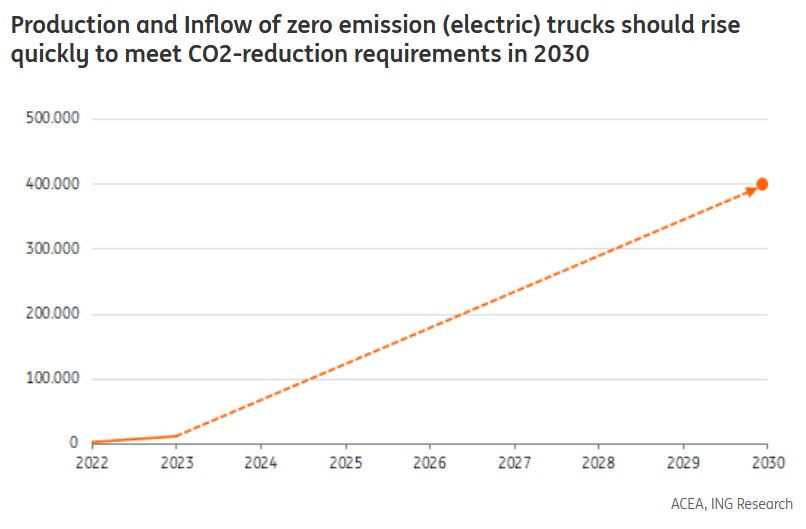

“Manufacturers must reduce CO2 emissions from their trucks to 15% by 2025 (versus 2019/2020) and to 30% by 2030. Earlier this year, however, Parliament and the Council agreed to sharply tighten this target. The targets are now -45% by 2030, -65% by 2035 and -90% by 2040. In the first few years, half of that progress will be achieved through improving diesel technology, but soon zero-emission trucks will have to take over. This means manufacturers will sharply increase their efforts to sell electric trucks,” he says.

“But carriers will also face pressure from shippers – their customers. This year, the CSRD directive came into force, requiring more and more companies to report their CO2 emissions. Also their ‘scope 3’ emissions, specifically the emissions in their supply chain. They will therefore ask their carriers to reduce their emissions. In addition, more and more cities are introducing ‘zero-emission zones’,” Ledent added.

To meet European CO2 targets, the installed fleet of zero-emission trucks will need to expand to 400,000 trucks by 2030 from less than 4,000 today. This means that the market share of electric trucks – now less than 2% – will have to grow by double digits very quickly. Not only purchase costs will therefore explode, but also operational costs,” he notes.

Transition logistics is also huge challenge

The energy transition has a direct impact not only on the transport sector, but also on logistics. Even in a context of mild recovery, profitability remains low, which in turn raises questions about financing the transition.

Philippe Ledent: “The relative fall in interest rates – not only in the short term but also in the long term – means that the financing cost of building new warehouses is improving. So we expect that, also thanks to the positive evolution of the economy and industrial activity, there will be more investment in new and more sustainable buildings. In parallel, investment should also be made in making existing buildings more sustainable, with solar panels, batteries and charging stations for electric trucks, and so on.

At the same time, investment in technology and automation is also needed, as productivity growth is imperative. This dual agenda is a huge funding challenge.”

Deglobalisation

Alongside the energy transition, deglobalisation is a trend that needs to be taken into account. “We have seen in recent years that unbridled imports from China have hit their limits in just-in-time. Today too, supply chains are showing their vulnerability, with the Huthi attacks in the Red Sea, for example. Companies’ supply chains are expected to change dramatically and so are logistics,” Ledent argues.

“Nearshoring we don’t see happening (yet), but we do see ‘friendshoring’. This means we will have trading partners in other countries and the number of suppliers will increase. This means that just-in-time supply chains will be harder to set up, which is likely to increase the average level of stocks held by companies. Also, rising protectionism – an evolution we can already observe in the US, with or without Trump – will affect supply chains and inventories and make them more expensive,” he said.

Financing becomes a headache

So those new supply chains will not only cost a lot of money but also require investment, on top of the massive investments needed for transition and automation. “And then the big question arises: who will pay for all those investments? And who can pay for them?” Ledent raises.

“In part, investments in the energy transition will have to be paid for by the government, like much of the infrastructure for example. But if we want to meet the objectives, logistics companies will also have to invest a lot more money in the transition. Where will they get the money? And will they have enough money to invest in digitisation, automation and robotisation at the same time? Possibly some companies will have to choose between either transition or modernisation,” he argues.